Fasten your seatbelts, Augusta, because Mr. Pearman’s Wild Ride starts at his Lake Olmstead house and ends with his artwork adorning Keith Richards.

AUGUSTA, GA. - Paul Pearman has lots of friends in Augusta. They don’t buy his art.

“They say, ‘You know, I went to high school with that fool. I’m not paying $400 for a belt buckle.’” Pearman laughs.

Of course, $400 is last year’s price. Pearman’s elaborately decorated buckles are so hot today that the prices have soared as high as $3,500 for his most detailed work.

That may explain why so few of Pearman’s fellow Richmond Academy graduates wear his work.

But Keith Richards has one. And Tanya Tucker. And Mötley Crüe singer Vince Neil.

“Paul ought to be bigger than Augusta,” said Molly McDowell, owner of the Mary Pauline Gallery on Broad Street.

He’s on his way.

Fairy dust

Pearman’s work at local boutiques, such as Soho and powerhouse bling-broker Windsor Jewelers, is only the beginning. The self-trained artist has become a star at trunk shows and arts festivals such as the Virginia-Highlands Festival. Late last year, he was scouted by chic boutique Fred Segal — frequented by celebrities such as Madonna and Lindsay Lohan. He was featured in the December issue of Lucky magazine and in the People magazine fashion show. He just finished interviewing with Southern Living about his home décor.

British luxury yacht designer and decorator Don Starkey, winner of several International Superyacht Design Awards, recently began using Pearman to design tiled interiors.

Starkey works on contracts for 75- to 200-foot yachts by companies like Alloy, Abeking & Rasmussen and Royal Van Lent. Pearman’s designs grace the interior bathrooms, kitchens and bedrooms of these floating palaces for clients such as Revlon billionaire Ron Perelman, Oracle Corporation founder Larry Ellison, Bayliner founder Orin Edson (he makes boats, but they’re small boats) and the Arisen family (who own Carnival Cruise Lines, so you wouldn’t think they’d need a bigger boat).

Pearman has also settled into a relationship with the influential Horn Fashions, with boutiques in Los Angeles and Berlin, whose stores are featured in In Style, Elle and Harper’s Bazaar. The shops are frequented by the likes of Cameron Diaz, Kate Winslet and Heidi Klum. Horn has outfitted the actresses of “Vegas,” “Charmed” and VH1’s “The Fabulous Life of the ‘It’ Girls.”

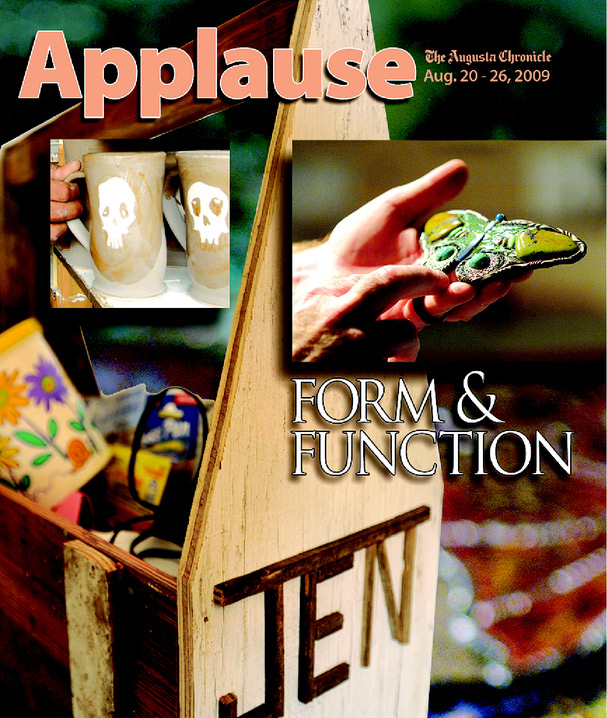

Pearman may brush celebrity fairy dust off his shoulders, but, if you saw him working, you wouldn’t recognize the celebrity. Most days, Pearman sits in his dungeon-like basement with his hair in a ponytail, wearing paint-spattered grey sweatpants and a T-shirt printed with “The Kiss” by Gustav Klimt. Friends say they’ve seen him wear it a hundred times.

He perches in a swivel chair at an old-school drafting table littered with dental tools honed to a fine point. His supplies are organized — sort of — on rotating shelves. A giant wall-mounted tack board serves as his filing system, featuring the remains of past projects and the models for future ones. When he holds an ornate butterfly belt buckle up to his mouth, I’m afraid he might tell me to rub the lotion on my skin or else I’ll get the hose again.

The only visible indication of his success is the flat screen TV on the basement wall across from him. It’s constantly tuned to nature-channel documentaries. He has this one about giant man-eating snakes memorized.

“Look at the size of that thing!” he exclaims, nodding his head at a reticulated python chomping on an unsuspecting police officer’s arm. “That’s a different kind of illegal alien, man. That’s not a busload of Mexicans.”

Conversations with Pearman jump like jackrabbits. He’ll talk about his wife, Michelle, then his two Dachshunds, Chloe and Pupster (who would very much like to eat the ankles right off your legs, thank you very much). He describes the weird lavender mushroom he found in his yard, his new property acquisition on the shore of Lake Olmstead and finally gets back to his artwork. He is exhausting and entertaining at the same time, like riding Space Mountain at the end of a long, hard acid trip.

Gallery owner McDowell said that it’s a strength that Pearman does not think in a linear fashion.

“He has childlike energy and enthusiasm,” McDowell said. “I think that there’s something that’s really charming about Paul as well, and that might be part of it, too. I work with a lot of quirky artists. His enthusiasm for his work and what he does is part of it as well.”

Perhaps because of the way his mind works, Pearman is not a member of the PC crowd.

He speaks his mind and despises what he calls “the milquetoast mentality.” It’s probably the kind of thing that kept him out of galleries when he was a young painter. That’s fine with him now.

“Galleries that would never have given me the time of day, now instead of me beating down their doors, they’re calling me,” he says, without a hint of reproach. Instead, he wears a dazed expression like the kind you see after someone’s had a brush with death or won the lottery.

“I’m an old man. I forgot to make money the first half of my life. But this money thing is really cool. I like money. I’m not used to it. Then I can buy cool saws and $1,500 worth of rare turquoise. This starving artist shit is for the birds.”

Origins of art

It didn’t take long for Paul Pearman to find art. At Richmond Academy, he often skipped biology and math to attend extra art classes. “Nothing was ever said about it,” he chuckled.

It took longer for art to find him.

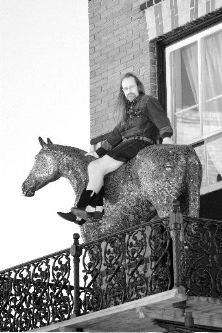

Pearman has always painted, heavily influenced by art nouveau, impressionism, Antonin Gaudi and Gustav Klimt. He tried for years to find gallery representation, not that it would have made much of a difference since he sold everything he painted. But a pass into the sometimes-hierarchical world of fine art is not often given to a skateboarding, kickboxing high school graduate.

He set a world record for the longest skateboard jump ever (over 26 barrels), as documented by the Guinness Book of World Records. He competed as a ranked amateur kickboxer with a third degree black belt, winning state and national championships belts. But all the while, he painted.

He did residential work, painting giant reproductions of famous paintings that his clients could never even think about bidding on if museums would part with them. An old refrigerator in a space adjoining his living room is covered with a hand-painted reproduction of van Gogh’s “Starry Night.”

“I used to literally copy van Goghs for a living. There were all these gay guys in Atlanta who just had to have van Goghs,” Pearman laughs.

The van Goghs paid the bills, and anyway, Pearman can never be called pretentious. He admits his influences. Heck, he built a business on them.

His painting was always inspired by the art nouveau movement’s stylized, curvilinear designs. His models: the patterns and textures in Gustav Klimt’s paintings, the Barcelona architecture by Gaudi and the forms found in the natural world. When he turned to mosaics, it was to Gaudi’s trencadis form of mosaics created from broken tile shards, also called pique assiette. Then he Pearmanized it.

Pearman makes his mania work for him. Traditionally, art nouveau works in nature with pictures of water lilies, seashells and dragonflies. Pearman’s work includes those and combinations of lunar moths, sunflowers, butterflies and… skulls. Well, skulls are natural.

Buckled down

“One day I was looking up at all them mosaics people were doing and I thought: ‘That looks horrible. They need to be thinking like a painter, because painting has rules,’” he says.

Painters begin with the foreground and build into the background. Mosaic is the opposite of painting: background first, foreground last. Dark colors first, light colors last. But unlike painting, mosaics can’t be done over, so Pearman must be design-minded.

“I hate random, broken color. I call that ‘soccer mom mosaic.’ You know: ‘Armed with a hot glue gun and a holster, here they come,’” He laughs.

It’s not that he has something against soccer moms. It’s that Pearman sees no room for error. With a floor installation, owners can’t be worried about a grandchild skidding over tiles that might cut bare feet. Adults don’t want to worry about slicing their hand on a fireplace insert and ruining a romantic evening. So Pearman’s tiles are grouted to stay — like Pompeii. Especially with the materials he uses, a secret epoxy weapon whose manufacturer just offered him free product in return for allowing them to use photos of his work. He declined. His secret would no longer be safe. No one can know the identity of the masked man.

“Basically, it’s just me by myself. I’m on the bench like the Lone Ranger for 20 hours a day. I work all the time,” he says.

Pearman’s belts are his mainstay, his bread-and-butter and his bane.

“I set out to make me a belt buckle, one belt buckle, and now look what happened,” he laughs.

Belt buckles aren’t cohesive to mosaic work. So he partnered with local metal sculptor Thomas Lyle (he taught local artist Chris Murray) to develop a spun metal edge for his buckles. The idea sprang from the old-school Spanish architecture that he loves so much.

“But it’s never been done on a belt buckle, at least as far as my lawyer can find. The hard part is design. Art is problem solving,” he says. And Pearman has spent his life solving problems. From how to jump 26 barrels with his skateboard to how to keep his ass (and his face) from getting kicked in boxing matches. Now his tenacity is paying off — and to some extent, ripping him off. Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, but it’s also the quickest way to hit an innovator’s pocketbook.

“If somebody sees the problems you have solved, it’s easy for them to emulate you,” he says. “That’s why I went for a copyright, a trademark and a patent. People are all the same; if they can find an easy way out, they will.”

It’s one of the reasons he doesn’t hire art students.

“You get some young art student kid and all of a sudden he’s like, ‘Hey, look what I figured out. I invented it,” he says.

It’s one of the reasons he’s stopped doing decorative home pieces like mirrors and clocks, because similar pieces began showing up in the galleries in which he sold his work. The artists would use glass or cheap materials and undercut him in price. The Tiger’s Eye, emeralds, shark’s teeth, nautilus fossils and koroit opals in Pearman’s work don’t come cheap. But they make an impact, McDowell said.

“He’s pushing it, so it’s edgier. You can go to any store and see big, chunky belt buckles, but he has a great sense of color and a great sense of materials,” McDowell said. “He’s got his design aspect down so well that then he gets to play with the concept. I think he’s going to do great, great, great if he keeps up the level of work he’s doing.”

And if the sincerest form of flattery is any indication of success, Pearman is already drawing imitators. A woman in Atlanta began calling herself the Mosaic Goddess and doing pieces that mimic Pearman’s work in a rougher, less refined manner. Her designs — which Pearman admits he didn’t invent — are so similar as to make one do a double-take. But put the two side-by-side and it looks like a child’s rough-edged drawing next to a master, like a schoolchild tried to copy da Vinci’s 1490 creation “Vitruvian Man.”

McDowell laughs when she thinks of people copying him. She said that people come into the Mary Pauline Gallery and frequently remark that they could duplicate whatever is hanging on the gallery walls.

“I tell them, ‘No, you can’t. You can’t do that because that’s not you. That’s not your soul; that’s not your person.’ Every time I’ve had someone try, they say, ‘Oh, it was miserable. I tried, it didn’t turn out well.’”

And the imitation hasn’t affected his sales. For now, Pearman complains he can’t keep up with demand. In advance of a holiday show in Chicago, he needed to make 400 buckles. A month before, he only had 100 because people kept buying them.

“I can’t keep a butterfly with a skull,” he shakes his head. “I tried to hire some people to help me, but it’s just not as easy for someone else,” he shrugs. “And I’m probably very hard to work for.”

Besides, in an art form that admittedly is nothing new, Pearman stands out. He strives for his glass to look like paint strokes and to have movement and direction. He has improved upon the technique, developed his own style and given a centuries-old method of expression a new life.

“He’s taken old concepts and old ideas and essentially hit a new level. Italy is loaded with these mosaics that are everywhere, but I think Paul’s got a whole new twist on it,” McDowell said. “I think it lives in his quirkiness as an artist, just taking it to another dimension.”

So he labors daily in his basement studio, surrounded by exotic semiprecious and precious stones. “Look at that,” he says, flashing a multicolored opal. “Have you every seen anything like that? It’ll hurt your feelings.”

Despite his excitement over new materials — skulls from a bone-carving shop in China, emeralds from Brazil — and his excitement about new contracts and a growing bank account, Pearman’s true love is in big installation pieces. He has two (shh!) public commissions coming up, but he won’t release details to the public because he worries about jinxing the projects. He’s afraid of the hoodoo?

“Oh, you know how it is,” he says, with a dismissive wave. “Nothing ever goes the way you want it to.”

His residential installation business is booming. One Columbia County riverfront homeowner, with quite the imagination and it seems more money than Midas, is having him design and install a concave floral glass mosaic on a staircase ceiling. McDowell herself has put her landscape architect on notice that Pearman’s design for a tile work patio insert takes precedence over the rest of the design.

“It’s really kind of changed the whole dynamics of the project and I’m so excited about it and my husband keeps going, ‘Oh, my gosh. What has this turned into?’” McDowell laughed.

But despite his residential success, don’t expect him to buckle under the pressure and spend his time reworking the Sistine Chapel.

“I really like the big projects, but the money is in the little pieces. I always joke that the name of this company should be Sin No. 3.”

That would be vanity. But perhaps a better choice would be gluttony. After all, buyers don’t just purchase one of his buckles. They buy new ones all the time. Pearman maintains a mailing list of past and present buyers, which does very well for him.

His success is still something of a shock to him. Years of skateboarding and kickboxing competitions didn’t give him much to bank on. So he won’t pass up the opportunities that roll his way.

“I never get off this bench and if I do get off this bench, I’m somewhere that I shouldn’t be. Wherever. I should be here. Because, you know, the light doesn’t always shine on you. I’m going to do this while I can.”

Visit newschoolmosaics.com.